Vignettes of Blue-Green Interventions in Mumbai

In Versova Koliwada, rising pollution and urbanization have led to the degradation of the creeks that have long been the livelihood source of the Koli fishing community. Forced to abandon traditional creek fishing, fishermen are pushed into deep-sea mechanized fishing, which requires greater investment and doesn’t necessarily promise returns. One can witness a similar story of climate challenges impacting urban communities across Indian cities.

From waterlogging and inadequate waste management to depleting groundwater and urban heat island effect, these challenges affect not just the quality of urban life but also carry implications for the livelihoods of marginalized communities. While the challenges experienced across cities are diverse and often hyperlocal, nature-based solutions (NbS), including blue-green infrastructure, are uniquely positioned to offer a tailored and wide-ranging approach for adaptation.

Why Mumbai Needs Nature-based Solutions?

Mumbai is the most population-dense city in India — half of its 12.44 million residents live in informal settlements and 65% work in the informal sector, with limited access to basic services.

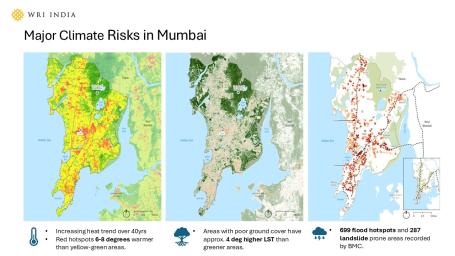

The city also faces rising climate risks. Urban heat island effect in Mumbai can raise temperatures in informal areas by 6–8°C. In the last two decades, the city has lost 40% of its green cover, further exacerbating these risks. Recognizing these challenges, the city drafted the Mumbai Climate Action Plan (MCAP), which outlines strategies to address climate risks, including through the promotion of nature-based solutions.

NbS interventions can succeed in remarkable ways, like Studio Piplikut’s efforts to convert a barren industrial plot into the Marol Urban Forest. By integrating solutions like wetland restoration, biodiversity enhancement and sewage treatment, Marol offers a replicable model for ecological and social impact.

To discuss learnings from more such NbS projects in the metropolis, share challenges and gather insights from practitioners, WRI India held a workshop in October 2024. Below are highlights and learnings from some of these projects:

Green Interventions in Underserved Neighborhoods

Focusing on green interventions in underserved neighborhoods, Youth for Unity and Voluntary Action (YUVA) and WRI India shared their experience in Lallubhai Compound — a resettlement colony in Mumbai’s M-East Ward — and Ambojwadi — in the non-notified parts of the informal settlement. To transform neglected plots in these localities to common spaces where people and biodiversity can thrive, these interventions were co-designed with residents, often led by women and children. While it led to improved accessibility, biodiversity and neighborhood resilience, challenges remained. Insecure tenure, institutional hurdles and resistance from developers highlighted the need for stronger policy support and long-term frameworks.

Community Efforts for Resource Equity

In Mumbai, almost 20 lakh people faced denial of water — most of them slum-dwellers — not due to actual scarcity but governance issues and tenure policies. The Pani Haq Samiti led a successful collaborative effort for the recognition of access to water as a fundamental right. Even as systemic hurdles, procedural delays, and entrenched biases continue to pose challenges, the success of the movement highlights the importance of sustained, evidence-backed and collaborative efforts.

Similarly, Stree Mukti Sanghatana (SMS) organized 5,000 women waste pickers into self-help groups (SHGs) across Mumbai, promoting decentralized waste management through composting and bio-methanation. Strategic interventions like these promise triple benefits of enabling livelihoods for women, reducing waste management costs and mitigating emissions.

These case studies exemplify the fundamental role that access to basic services like water and waste management plays in social inclusion and why we must incorporate them when proposing blue-green interventions. It also shows that social mobilization can ensure community participation in co-creating interventions to access these services.

NbS through Education and Mapping

The importance of participatory mapping efforts in NbS was highlighted by Mumbai Water Narratives and Tree Census projects, which illustrated the potential of community-driven GIS to inform planning and identify vulnerabilities. In M-East Ward schools, curriculum-aligned activities, eco-clubs and student-led transformations promoted environmental stewardship and climate literacy in a deeply localized manner.

Borrowing Indigenous Knowledge

Across the global South, indigenous communities have historically contributed to the restoration of natural resources. Koli communities have protected coastal ecosystems by employing traditional ecological knowledge for mangrove protection and maintaining marine biodiversity. NbS interventions are uniquely positioned to not just borrow from their traditions but also place these at-risk communities front and center while supporting the mainstreaming of these solutions.

The nationalization of the Sanjay Gandhi National Park (SGNP) led to the unintended displacement of many Adivasi people. The gap between the Adivasi perspective of the forest and the state’s conservation view requires a new, inclusive, and perhaps co-created perspective to shape solutions. A new approach that goes beyond considering the needs and rights of indigenous people to integrating indigenous knowledge.

The collaboration between the fisherfolk of Versova Koliwada and the Bombay 61 team under the TAPESTRY project suggests what this approach could look like. Through participatory mapping and dialogue, the team co-developed solutions with the community. Interventions included mapping waste hotspots, local experiments and community engagement events (seafood festivals and samvad khadicha (Conversations of the Creek)). They also designed and implemented a net filter system to reduce waste flow into the creek. A cleaner creek may lead to the return of the marine life that is the mainstay of the fishing community’s livelihood.

Way Forward

The blue-green framework workshop highlighted the potential of nature-based solutions in tackling climate risks, enhancing biodiversity and addressing urban challenges. While city-wide blue-green interventions are a work in progress, these insights from the ground serve as a record for reflection and highlight the importance of peer-learning and collaboration.

Local NbS initiatives show what is possible, but there is a need to connect these fragmented efforts to a city-wide blue-green framework. By aligning community action with institutional pathways, Mumbai can move from pockets of success to scalable impact. Enabling change that is inclusive, locally informed and integrated can not only help secure Mumbai’s climate future but also serve as a model to build cities that benefit people, nature and climate.

Read the complete conference proceedings here.